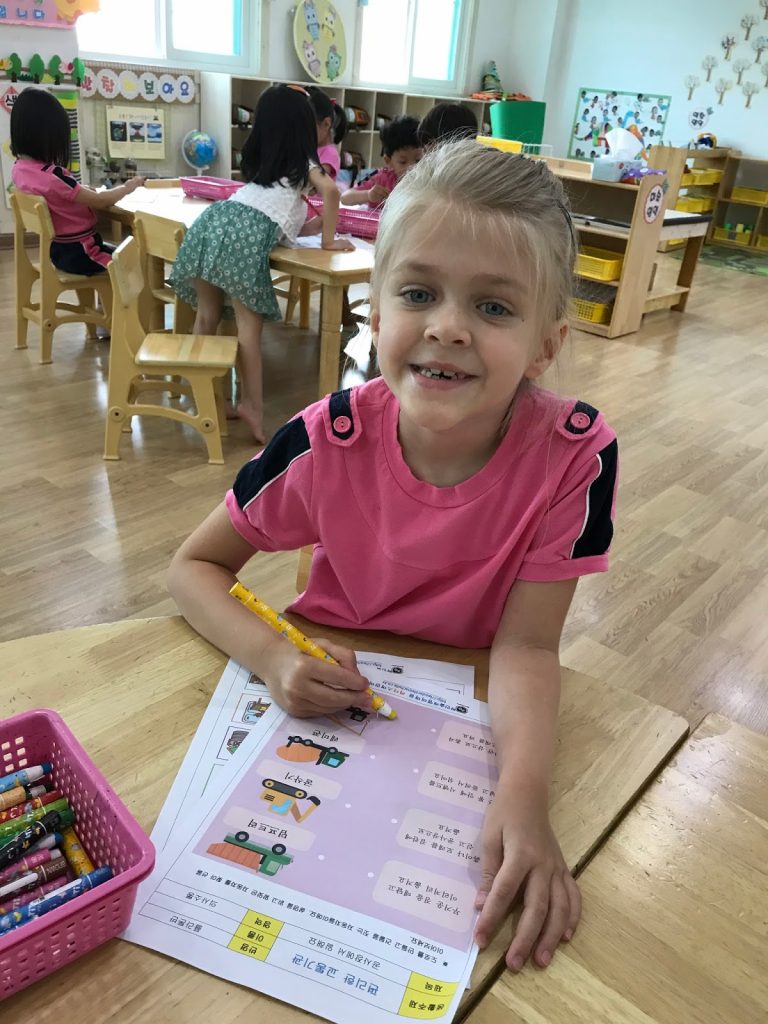

This week was the first week of the new Korean school year. Lena is now in the King Sejong 7-year-old class at Leaders Feinschule.

In case you are wondering why she is in the 7-year-old class, when she is actually only 5 years old, let me briefly explain the Korean age system…

In Korea, age is calculated slightly differently than elsewhere. When you are born, you are 1 year old, and you then add a year at each subsequent New Year. So, a baby born in December 2017 would today be “2 years old.” I’ve read several accounts explaining all this, with some differences. Some say they are simply including the gestation period in age calculation, some say they are counting “years involved” in your life (so those born in January 2017 and December 2017 would both count 2017 as a year in their age), some say you add a year on New Year’s Day (January 1), and some say you add a year on Lunar New Year. I imagine it’s a little bit of all that. This age calculation system is a traditional system that originated in China, so they originally added a year on Lunar New Year (remember the ddeok soup I discussed last year?). But now you can just use New Year’s Day, if you’re including calendar years involved in your life as part of your age calculation. Nobody really knows why Koreans still use this system when everybody else has since abandoned it (even North Korea supposedly stopped using it in the 1980’s). While the international age system is used officially in South Korea for government documents, legal restrictions and the like, traditional Korean age is still used in school and in most other situations.

Aside from that explanation, I mostly want to use this post to brag about Lena’s school. I just love this little school! It’s not that big, but they do so many interesting things and the education is very good, especially considering the fact that it is basically just a preschool or daycare.

Preschools in Korea are called 어린이집 (eorinijib), literally, “children’s house.” They have toddlers up to 7-year-old kids at the school, after which children enter the local elementary school. They follow the Korean school calendar, beginning classes in March and ending in February, with various breaks and holidays along the way.

When Lena started at Leaders in January 2017, she was 4 and she entered a 5-year-old class for two months until the new school year started in March. She spent this last year in the 6-year-old Plato class with about 20 other students. There are a similar number of students in her class this year, as well. At first, I only sent her a few days a week, then last fall, when she would have been entering a kindergarten class, I began sending her every day, but shorter days. Now I’m sending her full time, same as if she was attending the international school.

I should note, also, the reasons I’m not sending her to the international school, even though it would be much, much easier for us as a family if we did (due to different schedules). Initially, it was cost. The company only pays for education kindergarten and up, and the international school costs more per semester than I paid for four years at university (90’s pricing, not today’s pricing). By the time we could have switched her over, Lena was really enjoying her school and had friends there. Plus, her Korean was progressing well, since she’s prime age to learn a second language, and that’s a priority of mine. Leaders has an English language program for the Korean kids,* so Lena is actually learning to spell and read English. I didn’t realize this until last fall, when I thought, “Oh, she’s kindergarten now, I should teach her to read.” We sat down to read a book, but she read the whole thing to me, so… yeah, not a worry.

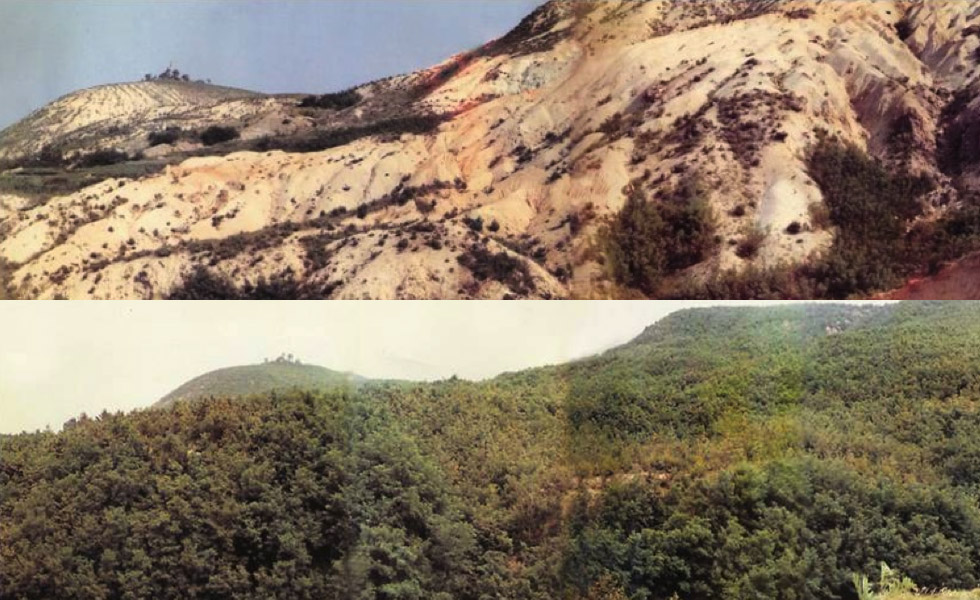

Leaders uses a variety of curriculum programs with input from parents. Since I don’t know the programs, I didn’t vote on them, but I’m pretty darn happy with what she’s learning. They study math, science, Korean/Hangul, English, society, art, etc, etc. All the usual subjects. Lena has a ballet class once a week, a music class once a week (last year they learned to play ukulele and drums), PE class once a week, a yoga-type class called “right figure” every other week. Once a month they have a cooking class in a special cooking classroom. During the summer, they got to swim in the basement pool, and the new PE teacher said they will have swimming lessons this year. They go on interesting field trips to plays, museums, and farms about once a month, and when the weather is nice they go on “forest walks” every Friday to experience nature. This January, they even had the kids perform song and dance numbers at the local cultural center. And during Korean holidays, the kids dress up in hanbok and play traditional games.

Lena’s teachers have all been incredibly sweet and helpful. They’re very accommodating of my lack of Korean (though this is all impetus for me to learn), and they do a good job of communicating regularly and sending pictures when the kids do fun things.

Seriously, it’s such a nice little school.

Unfortunately, there is one big problem with the school: summer break. Or, rather, the lack of a summer break. I’m honestly not yet sure what I’m going to do this summer, when Connery doesn’t have class but Lena does, because she’s not going to like that one bit. So, I can either take her out of school for two months, or I can find a bunch of programs to put the boy in. I’d prefer the latter, if I can find something that will help him learn more Korean, but I’m not sure if that exists. It’s going to take a bit more research before I can figure out what to do.

*Korea is in the midst of a debate about its English-language programs for young children. The Education Ministry passed a law in 2014 that banned after-school English classes for kids in 1st and 2nd grade. The law was challenged by students and parents at an elementary school in Seoul, but was upheld by the Constitutional Court. After a 3-year delay, the law went into affect last week. They also extended the ban to kindergartens and daycare centers, although that part of the ban has been delayed until next year. English classes officially begin in public school in the 3rd grade.

There has been a huge outcry about this ban from parents and teachers. To start, thousands of Korean English-language teachers are losing their jobs. Secondly, the public after-school English classes were relatively affordable, around $50/month. Now, those who want their kids to learn English must put them in private schools that cost 4 times that much. In the highly competitive education environment that is Korea, this basically means that rich kids will get farther ahead and poor kids will suffer.

There’s a lot of politics involved in all of this, between the previous and current governments, between public schools and private schools, and between nationalists and those who want to be internationally competitive. The law was based on “experts” who claim that learning two languages at a young age is too “stressful” and confusing to children, and “educators” who think they should focus on Korean proficiency first.

I’m going to have to agree with the 71% of Korean parents and 68% of Korean elementary schools who think this ban is a dumb idea. Real experts, not politically leveraged ones, agree that the best time to learn a second language is before the age of 6-7, or maybe until age 10. By age 12, your brain is pretty much done forming and you lose out on the ability to grow extra synaptic connections. Waiting until grade 3, and then offering only an hour a week, isn’t going to do near as much as the programs they’re banning. And why should they care, anyway, when it’s such a popular program among schools and parents? It all smacks of nativism.

And it reminds me of a story I read a few years ago about Chinese language immersion kindergartens in America. The Chinese government was helping fund them as part of its “China is awesome!” charisma campaign. They were your basic public kindergarten programs, but half the day was taught in English, and half was taught in Chinese. I thought it was a fabulous idea: if you can speak English and Chinese, you’ve got your foot in the door for a whole host of languages. Who wouldn’t want their kids to learn Chinese, especially if it was offered for free? Well, apparently, a bunch of people. “It’s America; our kids only need to learn English,” was a frequent reaction.

I’m not going to mince my words here: those people are morons. In the era of the internet and globalization, our kids are going to be competing on a global scale. Being bilingual will give them a boost for a variety of future job opportunities. Plus, studies have shown that it’s easier for bilingual adults to learn a 3rd or 4th language than it is for monolingual adults to learn a 2nd language.

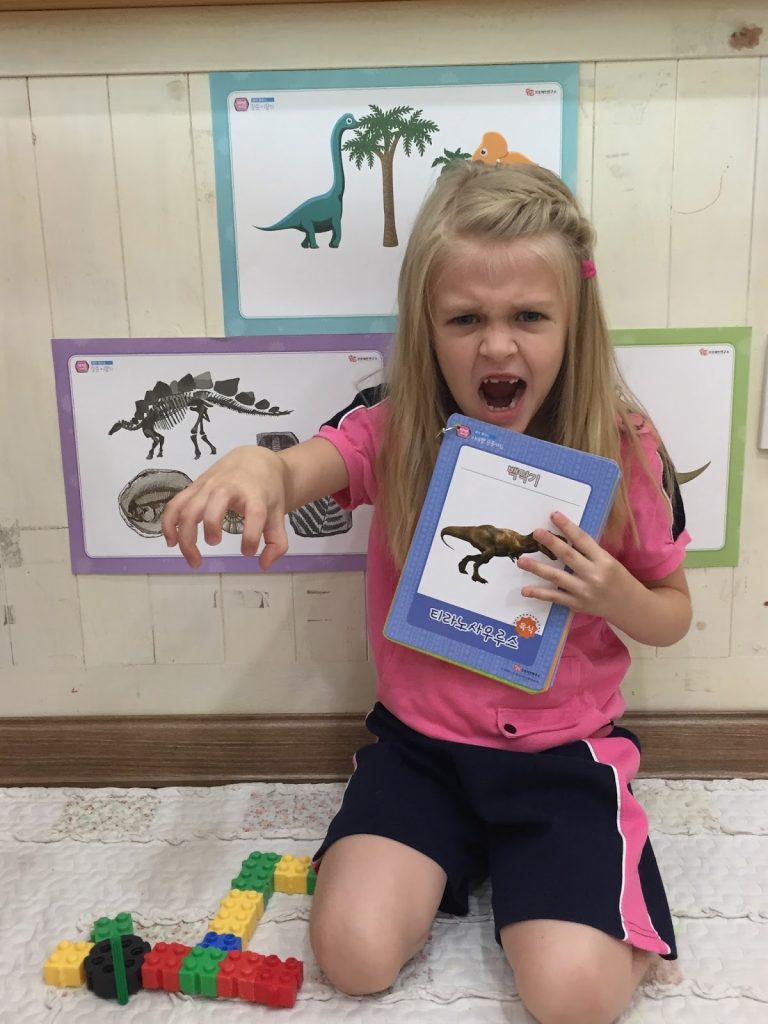

And as for that “stressful and confusing” argument: I took my 4 year old English-speaking daughter and threw her in a Korean-language school with basically no life preserver. Yes, it was a bit stressful at first, but she didn’t burst into tears and run away to hide behind the playground equipment like my son did at his English-language school. New schools are stressful in any language, but kids are adaptable, and both of mine are doing great now. So pbhtth on that.