Monday was Hangul Day, the day that commemorates the creation of Hangul (or Hangeul), the Korean script.

As an English speaker, I’m guessing that this…

안녕하세요? 초콜릿 먹실래요?

Looks to you like this…

gobbledygookgobbledygookgobbledygook

But, in fact, what you are looking at is one of the most clever writing systems ever created by humans. (And please note that I am speaking about the writing system only; Korean itself is a beast of a language, what with its multiple levels of formality and honorifics, need for contextualization,* and “feelings” instead of hard and fast grammar rules.**)

Why is Hangul so clever?

Well, first, because it is a created script – a scientifically created script, no less. Unlike most language writing systems, which evolved over time, Hangul was created in one go, specifically for the Korean language. Every sound has its own character and it’s consistent. None of this “through = thru” crap English speakers have to worry about, or “do I pronounce the H in herb?” kind of problems.

Second, because it was specifically created to be easy to learn.

A little history before I explain the technicalities…

In the early 1400’s, Korean was written using a mishmash of Chinese (derived) characters called hanja and various native phonetic characters. This is similar to Japanese today, which is a mix of kanji (Chinese characters) and hiragana/katakana (phonetic characters). About 70% of Japanese words and 65% of Korean words originally come from Chinese (in Korean, they are known as Sino-Korean words) and can be written with Chinese characters. But the problem with Chinese characters is that they are difficult to learn — they are not intuitive and require lots of time to memorize. In 15th century Korea, only a small, elite class of scholars were literate because of this.

Then came King Sejong the Great, fourth monarch of the Joseon dynasty. Sejong did a lot of amazing things to secure his country and make life better for its people. He overlooked class when choosing skilled people for various jobs (much to the distaste of elites), he promoted science and literature, he strengthened the military, he reformed taxes on farmers to ease their burden and create a surplus of rice for the poor… he was very much a forward-thinking person. But probably his greatest achievement was the creation of Hangul.

Together with his son and a small group of scholars (though some argue he did it himself, as he was an accomplished writer), Sejong sought to create a writing system that would be easy for the vast number of illiterate farmers and peasants to learn. The Hangul alphabet was finalized in 1443, and its date of publication in 1446 with a manual called Hunmin Jeongeum (“Proper Sounds for the Instruction of People”) is today celebrated as Hangul Day.

Regarding ease of learning, the Hunmin Jeongeum claimed, “A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days.” I can testify from experience that this is true. Before moving to Korea, I put a really plain app on my phone that teaches you the letters, along with their sounds, then quizzes you. I was reading basic words within a couple days of using the app for just 20 minutes at bedtime. I often had no idea what the word meant, but since a lot of English words appear in Korean everyday use (especially in chain restaurants), just knowing Hangul helped tremendously.***

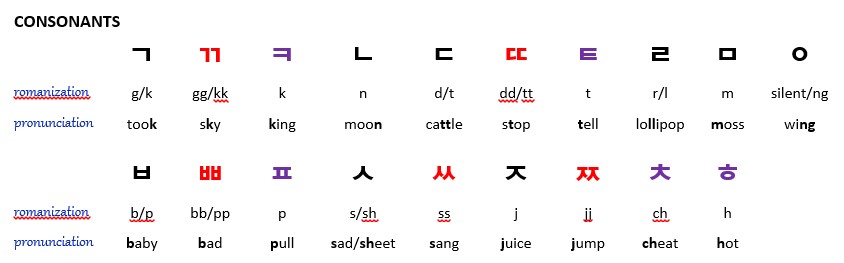

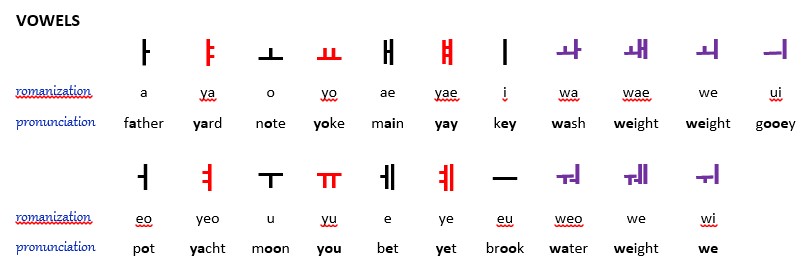

Let’s take a little detour to introduce letters.

Don’t ask me about tense or aspirated consonants, because I cannot hear a bit of difference between them. They are supposed to be stressed or emphasized or go up in pitch or have more force of air behind them or something like that, but they all come out of my mouth the same. 방 (“bang”) and 빵 (“bbang”) are both “bahng” to me.

Letters are combined into “blocks” to create a syllable. Blocks must contain either a vowel with the placeholder ㅇ before it (vowels cannot be first in a block) or a consonant plus a vowel. Blocks usually have 2-3 letters, but can have up to 4-5 (full disclosure: I hate the 4-letter blocks). These blocks can be words or combined to make words.

So 사 “sa” + 람 “ram” = 사람 “saram,” which means person. (사 is also the Sino-Korean number for 4, but numbers are a subject for another day.)

Go ahead and try making your name from the letters above. Mine is 메간. Lena is 리나. Jennifer is 제니퍼. And Robert is 로버트.

Easy, right?

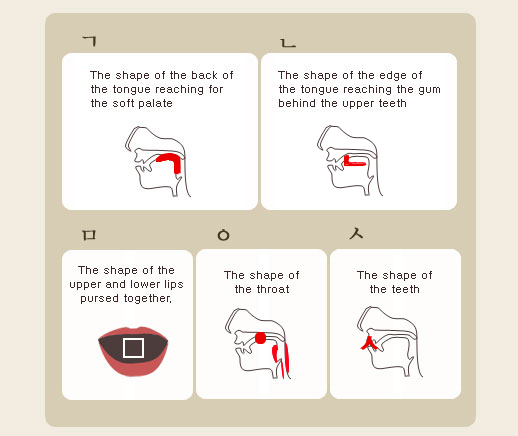

Well, okay, there’s more to it than that. In fact, there’s a whole lot of fancy linguistic terms used for why this system was well designed. I won’t bother with all that, but one fun example of Hangul’s clever design is this: the shape of the letters were meant to be memory cues. Consonants mimic the position of a person’s tongue in the mouth when it is making that sound.

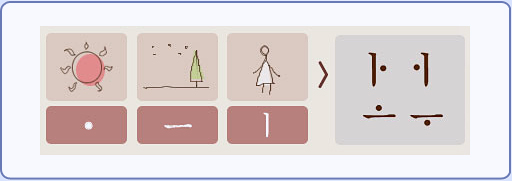

And vowels were designed as horizontal and vertical lines representing earth and human, and the little lines that jut off to the side were originally dots, representing sky. This not only helps make vowels easily distinguishable from consonants, but also represents a yin/yang philosophy of darkness and light. Vowels pointing up or to the right (ㅗ and ㅏ) are light and those pointing down or to the left (ㅜ and ㅓ) are dark. Light vowels combine with other light vowels, and dark vowels combine with other dark vowels, something known as vowel harmony (the Korean language already had strong vowel harmony). In Korean, words with “dark” vowels tend to represent a darker or heavier meaning, compared to those with “light” vowels.

The publication of Hangul had the effect King Sejong intended. Within a relatively short time, a large number of Koreans could read it. That’s not to say Hangul didn’t have a rocky path to prominence, however. The literate elite opposed the new alphabet. Subsequent (less benevolent) kings did not like peasants putting up posters mocking them, so banned the script. Its use came and went over the centuries, usually still mixed with hanja. It wasn’t until the late 1800’s that Hangul was used in an official capacity. And it wasn’t until the 1980’s that hanja began to fade from use. Today, almost all written text in South Korea is in Hangul. (North Korea switched to Hangul at its founding after the war.)

Hanja is still taught in schools here, and there are those who wish to bring it back. Personally, I think that would be stupid. Why take such a fabulous and well-designed writing system and replace it with something unnecessarily difficult and unsuitable. I’m all for maintaining traditions, but some traditions we just don’t need anymore.

*Koreans don’t really use a lot of pronouns; you just kind of have to understand what is being discussed by context. “You,” for example, is 당신 “dangshin.” But even though this is the only word for “you,” it is considered to be overly aggressive, so you’re not supposed to use it unless you’re looking for a fight.

“Well, what if we want to refer to something that belongs to you? Like, ‘your baby’? ‘As in, Your baby is cute,'” we asked our language instructor.

Teacher: “Just say, ‘baby is cute.'”

Aaron: “What if there are two babies? And one is ugly, but yours is cute. I want to say your baby is cute.”

Teacher: “You would never do that. Never. All babies are cute.”

Aaron: “But…”

Teacher: “NO. All babies are cute.”

**While there are many specific grammar rules for Korean, there also are a whole lot of phrases and sentences that are composed a certain way for seemingly no particular reason. I would often ask our language teacher if “xyz” was correct, and she would say, “No… that doesn’t sound right, you should say ‘abc,'” even though there didn’t seem to be any particular rule against “xyz.” Or I would ask her why something must be said a certain way, and her response was, “Well, it just doesn’t sound right.”

At first, I thought it was just me, but I recently read an article in which a native English-speaker university professor who lives in Korea discussed arguments with his Korean teacher over phrases that “just don’t feel right,” even though the teacher could not explain why.

***Learning Hangul is so easy, I believe it lulls one into a false sense of ability when it comes to learning the Korean language. The script can be read in a day or two; to understand its meaning takes years. The U.S. Foreign Service Institute lists Korean as a Category V learning difficulty for English-speakers (the hardest category, requiring 88 weeks to learn). Spanish, by contrast (the language I studied all through school) is Category I (24 weeks).